Observer Name

Craig Gordon

Observation Date

Sunday, February 10, 2019

Avalanche Date

Saturday, February 9, 2019

Region

Uintas » Upper Weber Canyon » 1000 Peaks » Chalk Creek

Location Name or Route

Blue Lake

Elevation

10,300'

Aspect

Northwest

Slope Angle

38°

Trigger

Snowmobiler

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Hard Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

5.5'

Width

1,000'

Vertical

500'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Injured

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

From a historic perspective this area claimed the lives of two snowmobilers on March 10, 2001.

Saturday February 9th, 2019-

Jason joined Shannon and his son Jessie for a day of riding in the Chalk Creek drainage. They planned on sticking with low angle terrain and meadow riding. Shannon and Jason wore avalanche beacons, Jessie did not. On their way out of the area they decided to play on a slightly steeper slope, about a mile south of Humpy Peak. Both Jason and Shannon took turns climbing the slope which was connected to steeper terrain above. After his third climb, Shannon and his son Jessie posted up on a relatively flat bench feature and watched Jason climb slightly higher than the previous attempts. Shannon watched Jason climb towards the uphill side of a dead tree low on the slope, and was alarmed when he noticed Jason's weight shift to the downhill side of his sled, like he was getting knocked off his snowmobile. Shannon looked up at the ridge above and witnessed the steep chutes beginning to avalanche. He tried to keep and eye on Jason, but was also worried about his sons safety and attempted to get his attention and alert him of the situation. As Shannon realized the enormity of the avalanche, both he and Jessie throttled their machines and headed to the west out of the slides path.

Once the dust settled Shannon rode to the last seen point, jumped off his sled, and began a beacon search. He had difficulty switching his F1 beacon to "receive", so he powered down the unit, and then reactivated it, but may have erroneously engaged his beacon to "send" mode. There was some signal confusion and Shannon thought his batteries were dead so he quickly changed batteries and continued his search. At some point Shannon realized the enormity of the situation and activated his SPOT locater. He searched the debris pile, zigzagging below the last seen point and keyed into the first signal about 15 minutes after beginning his search. Shannon didn't have a probe, but he and Jessie began digging where Shannon heard the strongest signal. They dug but didn't see any clues and began trenching to what they thought was a likely burial area. As they were digging a group of two snowmobilers arrived. They had probes and shovels, but no beacons. They began probing and within a few minutes one of the probes struck Jason and they began digging him out. Jason wasn't breathing when the group extricated him and Shannon began CPR for approx. 30 minutes before a DPS helicopter arrived on the site.

Timeline-

13:05- Call from Airforce Rescue Center

13:20- Summit SAR activated

13:34- DPS Pilot notified

14:15- Approx time Jason is dug out of snow and CPR begins

14:28- DPS Crew in Star 9 launch

14:55- Heli lands at the GPS coordinates

15:00- Jason on board aircraft with heli enroute to Evanston Hospital

15:14- Landed at Evanston Hospital

15:18- Doctors called the time of death due to traumatic injury.

Burial details-

Jason was carried approx 100 feet vertical but 380 feet slope distance.

He was buried at 40.85772 -111.01588, elevation 9900 feet,

He was 15 ft directly uphill of the buried sled

Below.... Shannon tells the story in his own words.

Terrain Summary

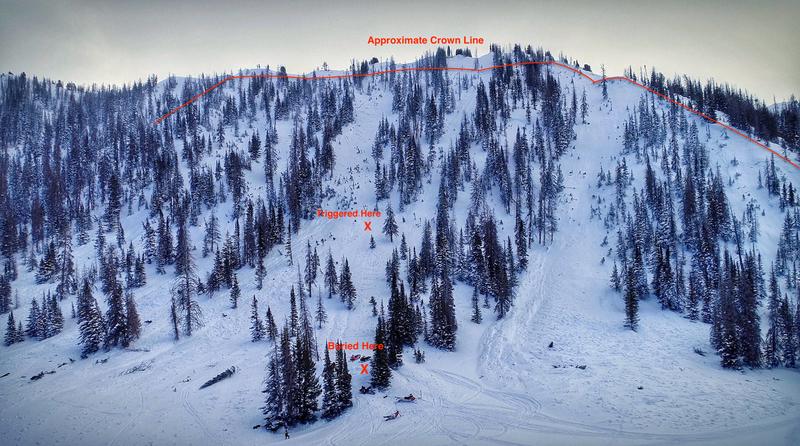

Looking up the path from close proximity to where Shannon and Jessie retreated.

Terrain is comprised of a series of steep chutes and hanging snowfields facing north and northwest. This image is about 1/2 way up one of the chutes that avalanched and accurately represents the terrain features. Crown profile was taken in this chute near the ridgeline.

Looking down path. Jason was buried in the adjacent runout of the chute to the north (skiers right).

Weather Conditions and History

Historically weak, shallow, and dangerous the Uinta snowpack often resembles the structure and strength of a Continental, rather than an Intermountain snowpack. It's not unusual for the western Uinta's to develop a sugary, basal layer near the ground that never heals and remains problematic or persistent for the entire season. As a matter of fact, it's more the rule than the exception. However, the winter of 2018-19 has been slightly different, characterized by a more consistent storm track, delivering more storms and denser snow with higher water content, or SWE. Avalanche forecasters measure snowfall in terms of inches and feet of snow, but more importantly the snow water equivalent (SWE). In other words, it's how much water the snow contains. If you melted the snow, how many of inches of water would it be. From an avalanche perspective, we don't care how much snow fell. We care how much weight was added to the snowpack. More weight = more stress. The more you stress something, the more likely it will break. When the snowpack is stressed and breaks, it produces avalanches. A rough guide is that 1 inch of SWE is about 10-12 inches of snow.

OCTOBER/NOVEMBER-

Late October snow helped set the tone and the building blocks of our winter snowpack, but consistent snow didn't begin to stack up in earnest until Thanksgiving when a cold, robust storm system delivered two feet of snow with 2" of H2O or SWE. Another 10" of snow with an inch of H2O rounded out the month.

DECEMBER-

Unfortunately, the pattern became inconsistent and weak storms along with strong winds became the dominant theme of the December weather pattern. As a result, the snowpack remained relatively shallow and grew weak, producing faceted, sugary snow both at the surface and near the ground. A small Christmas storm did little to turn the tide and the end of the year was punctuated with an unusually strong East-Northeast wind event that created a hard, dense slab which formed on top of the pre-existing weak surface snow.

JANUARY-

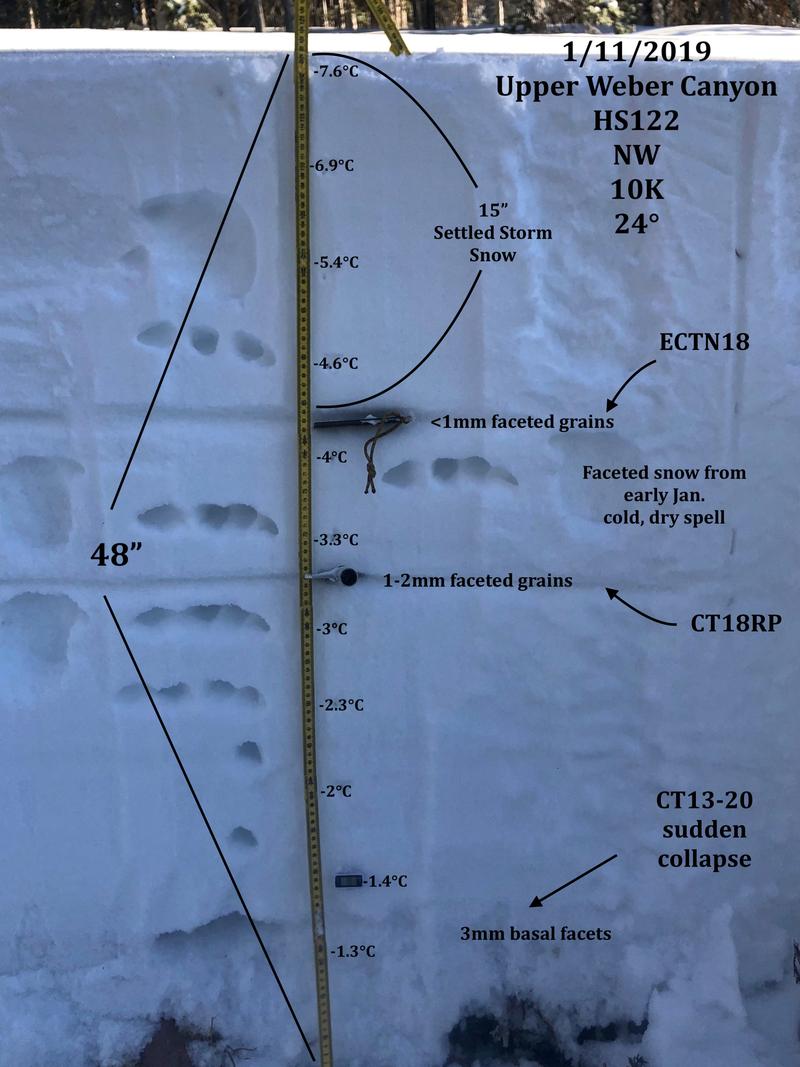

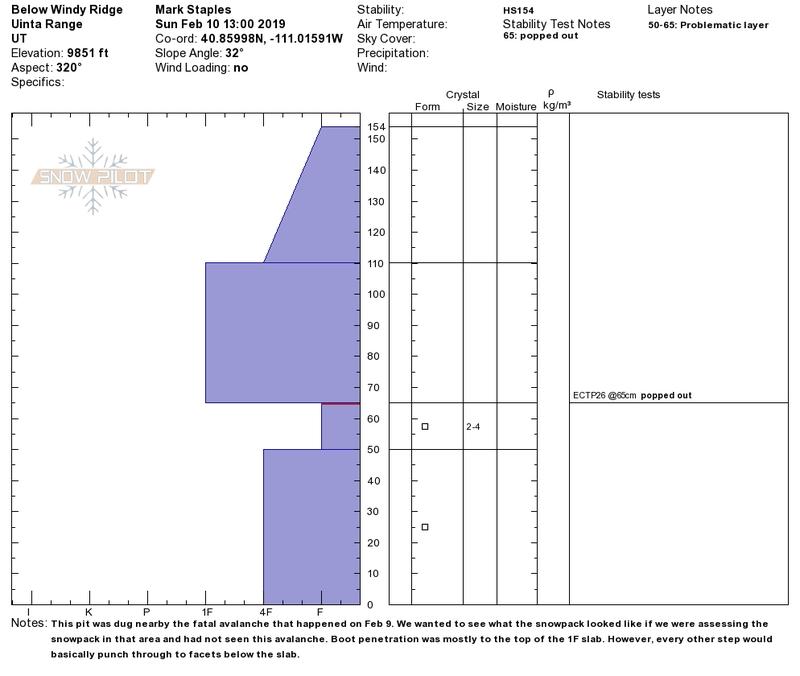

On January 7th, a warm, wet, and windy storm slammed into the region delivering 18" of snow with nearly 1.5" of SWE, and very strong west-southwest winds. A thick, dense layer of snow grew on top of the New Years wind slab. Most avalanche activity could be characterized as "pockety", but one large avalanche breaking to the ground (pictured below) in upper Weber Canyon made me realize the potential this disastrous layering could deliver. In addition, our snowpoack sturcture suggested a sketchy setup as illustrated in a nearby snowpit profile (pictured below)

January 18th brings yet another round of dense, heavy snow. 18" with 2.25" SWE along with very strong southerly winds clobber the range and an Avalanche Warning ensues. This storm is the tipping point, bringing the snowpack to a critical threshold and avalanches begin failing near the midpack New Years slab and then quickly break to the ground where the snowpack remains thin and weak. This snow, water, and wind event also leads to a string of human triggered avalanches in the western Uinta's and a number of close calls, but fortunately no accidents. However, the writing is on the wall and one thing is clear... each time the snowpack receives a substantial amount of SWE, the pack comes to life and avalanches conditions light up.

These snowmobile triggered slides triggered in late January, accurately represent the depth, width, and magnitude of the type of avalanche conditions inherent with the snowpack for the western Uinta Mountains.

February-

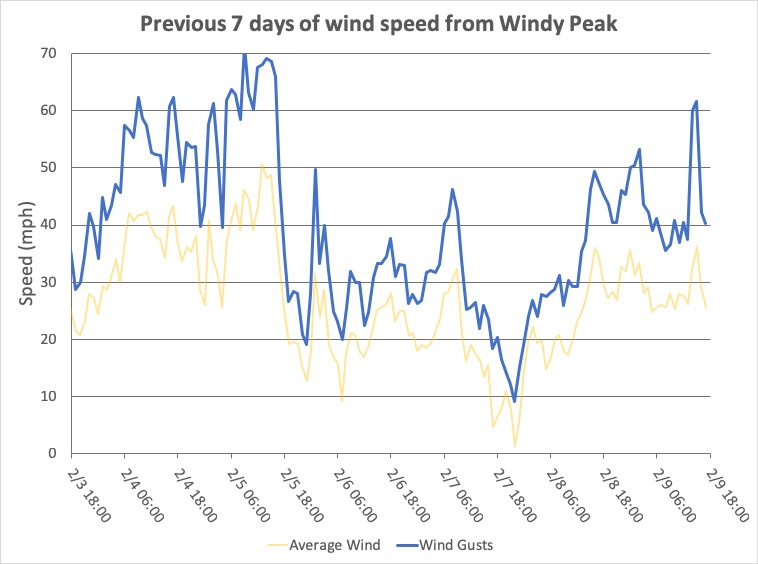

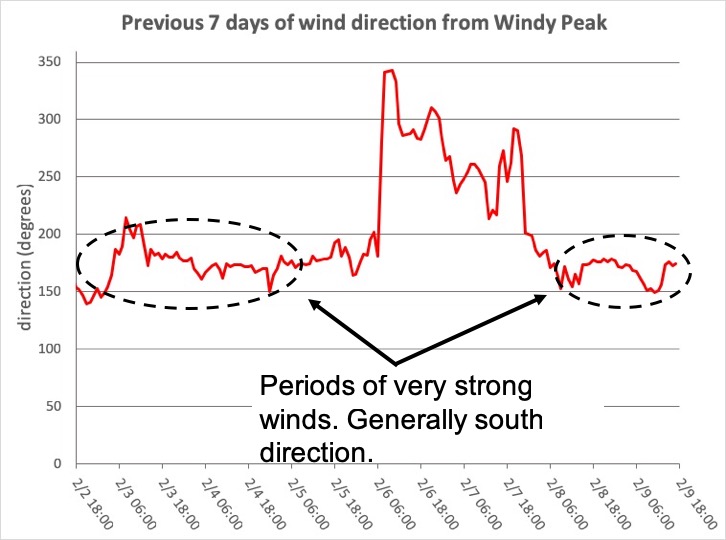

A very wet, warm, windy storm materializes on the evening of the 2nd, delivering 2" of dense, heavy snow, along with southerly winds blowing in the 30's and 40's. An additional 18" of snow along with 2" of SWE stacks up on the 3rd with continued strong ridgetop winds. South and southeast winds blow in the 50's and 60's through the 4th. An additional 4" of snow with .50 SWE stacks up in the early morning hours of the 6th and southerly winds continue to blow in the 40's. The storm finally winds down on the 8th with storm totals delivering a whopping 38" of snow and 3.4" of SWE.... a colossal amount of snow, water, and sustained winds.

FEBRUARY 9TH

WEATHER DAY OF ACCIDENT-

The morning starts of with a layer of high, thin clouds and a few snow flurries. And while snowfall tapers off, southerly winds continue howling along the ridges, transporting snow onto mid and upper elevation, leeward terrain, especially slopes facing the north half of the compass. We are in-between storms and by mid afternoon the winds increase slight and it begins snowing. Weather didn't necessarily play a role the day of the accident, it was actually the weeks worth of weather beforehand, but it definitely complicated the logistics of the rescue. Had it been later in the day, chances are the DPS helicopter would have had a difficult time assisting in the recovery efforts.

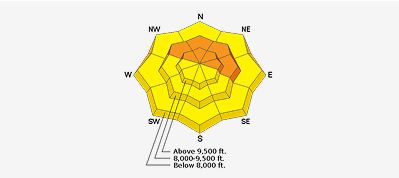

Above.... the avalanche forecast for the day of the accident along with winds from Windy Peak.

The Chalk Creek #1 SNOTEL is 2 miles west-southwest from the accident site at an elevation of 9,171 feet.

The Windy Peak station is 1 mile south of the accident site on top of Windy Peak at 10,662 feet.

Comments

Above... images of crown and crown profile.

The snow profile above is from a sheltered location just downhill of the accident site. The purpose of this pit was to gauge how representative the crown profile was. It looks fairly similar and the snow depths match quite well.

Comments

These three images were taken by DPS staff as they assessed the scene from the air and then again on the ground.

Coordinates