Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Sunday, January 31, 2021

Avalanche Date

Saturday, January 30, 2021

Region

Salt Lake » Park City Ridgeline » Squaretop

Location Name or Route

Square Top

Elevation

9,400'

Aspect

Northeast

Slope Angle

37°

Trigger

Skier

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Type

Soft Slab

Avalanche Problem

Persistent Weak Layer

Weak Layer

Facets

Depth

2'

Width

125'

Vertical

250'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Buried - Fully

1

Killed

1

Accident and Rescue Summary

This photo shows the avalanche on the lower right side of the mountain.

On Saturday, January 30, Kurt Damschroder, a 57-year old male from Park City, Utah, was killed in an avalanche on Square Top Peak along the Park City ridgeline in the backcountry adjacent to Canyons Village of the Park City Mountain Resort (PCMR).

Kurt and his partner read the avalanche forecast for that day and were very familiar with the area, having skied there for many years. They took 2 previous runs in the backcountry using the 9990 chairlift at PCMR for access. Their first and second runs were just south of Cone Head in the Owen's Line area. Both runs are about 0.6 miles to the south of the 9990 chairlift. They did not see any avalanches, cracking, collapsing, or other signs of unstable snow. They both carried avalanche rescue gear (transceiver/probe/shovel), and they did not dig a snowpit at any point during the day.

For their last run in the backcountry, they rode the 9990 chairlift, exited the resort through a gate, and entered the backcountry to ascend Square Top, a peak about 0.5 miles to the north. At approximately 3 p.m., they descended a ridge known as "Square Top Sneak." Approximately 2/3 of the way down the ridge, they stopped to discuss where to go next, as marked in the photo below. Kurt wanted to descend a relatively short 37 degree slope below them, and his partner did not. His partner wanted to stay on the ridge for the final portion of his run. The pair decided that the partner would wait and watch Kurt while he descended before skiing an alternate route down the ridge and and regrouping below. The avalanche occurred just as Kurt entered the slope before he had a chance to turn downhill. He was caught, carried, and almost fully buried in the avalanche.

Locations where Kurt and his partner discussed whether to ski the slope or not and where Kurt was when the avalanche released.

His partner witnessed the avalanche and determined it was too dangerous to enter the avalanche path from the top of the slide. He then descended the ridge aiming to enter the avalanche path at the point where he last saw Kurt. He put climbing skins on his skis after reaching the debris, not knowing if he'd have to go uphill or downhill to reach Kurt. At 3:20 p.m., the partner called PCMR Ski Patrol and began a transceiver search. His partner assumed Kurt was downhill and soon acquired the signal from Kurt's transceiver with an indicated range of 60 meters.

As he got closer to Kurt's location, he spotted part of a ski boot sticking out of the avalanche debris and began digging. Kurt was found on his right side with his head upslope buried 3-4 feet deep. The partner uncovered Kurt's face and was able to give rescue breaths. Before the partner could move Kurt to begin CPR, he had to dig much deeper because Kurt's right arm was stuck deeper in the snow attached to a ski pole with a wrist strap. The partner contacted the PCMR Ski Patrol during the process and began CPR at 3:40 p.m.

View from the avalanche crown face with the location where the partner last saw Kurt. The last seen point is important to note during a rescue because it narrows the search area as the victim will only be below that point.

The partner noted being tired before they began their descent of Square Top. Searching, digging, and performing rescue breaths/CPR for 30-45 minutes left him exhausted. PCMR Ski Patrol and the Summit County Sheriff's Office asked him to leave the scene so that they could begin recovery operations. Because much of the terrain had not avalanched, PCMR Ski Patrol and the Summit County Sheriff's Office determined that avalanche mitigation was needed to reach the accident site safely. Due to the encroaching darkness, the recovery mission was suspended until Sunday, January 31.

On Sunday morning, the Department of Public Safety (DPS) and PCMR Ski Patrol conducted an avalanche mitigation mission using explosives deployed from a helicopter. Three additional large slides were released on the slope adjacent to the avalanche accident. Following this mitigation work, rescue personnel from the Summit County Sheriff's Office recovered the victim from the avalanche site. There were no obvious signs of significant trauma.

The avalanche was classified as SS-ASu-R1-D2-O

The burial location was 40.667542-111.599789

Avalanche location with notes where the skier entered the slope and was buried 250' lower.

Accident site following mitigation work.

Ascending the debris towards the burial site.

The burial site. The victim's head was buried approximately 3-4 feet deep.

Looking down from the top of the avalanche. The slope measured 37 degrees in steepness, and the burial occurred 250 feet lower.

Terrain Summary

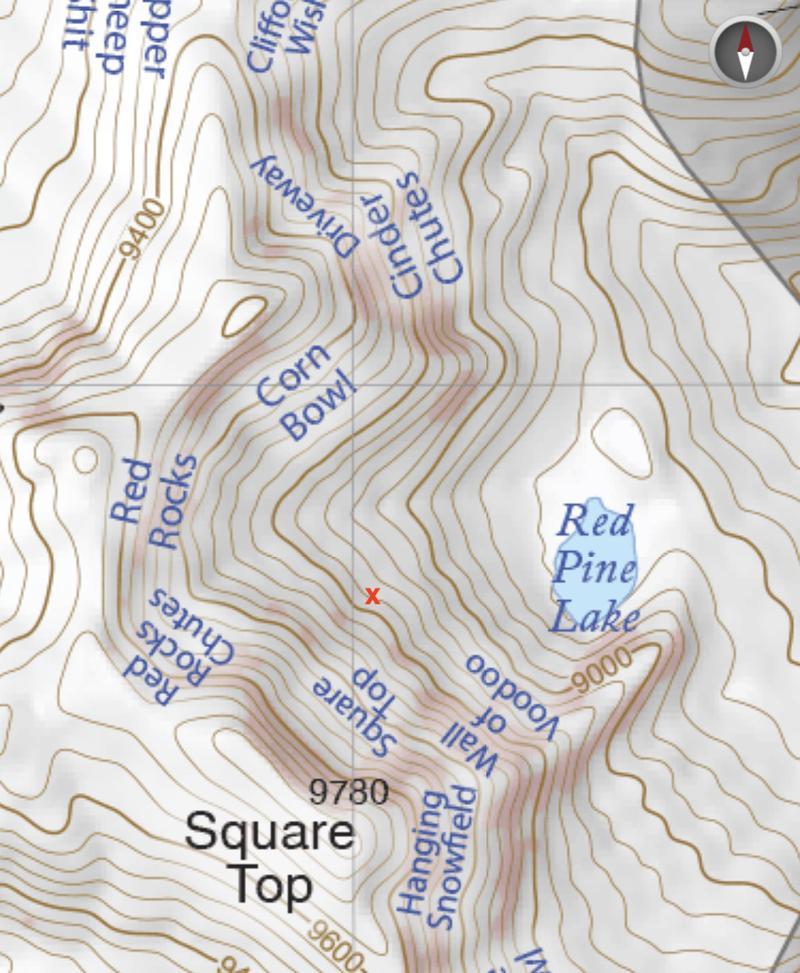

Square Top Peak is backcountry terrain along the Park City Ridgeline and adjacent to Park City Mountain Resort. The map below (from Wasatch Backcountry Skiing map) shows an overview of the area, and the X marks the approximate location of the accident.

Weather Conditions and History

On the day of the accident, the avalanche danger was rated as HIGH for northeast-facing terrain above 9,500 feet and CONSIDERABLE for northeast-facing terrain between 8,000-9,500 feet. The slope on which the fatal avalanche occurred faces northeast at 9,400 feet. The avalanche forecast for the day can be found here.

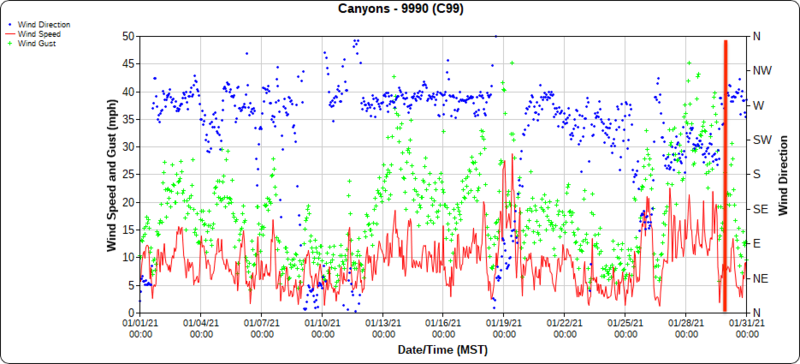

For much of the winter, the Wasatch mountains received minimal snowfall, with nearby SNOTEL sites recording a snowpack about 60% of average as of the day of the accident. A layer of weak faceted snow formed during periods of dry weather in November and December. Strong winds blew from the southwest on Thursday, January 28, with gusts over 50 mph. In addition, there were two minor storms during the week before this accident totaling 3" of snow. Two skier-triggered avalanches occurred on nearby slopes, one on Monday, January 25 on Squaretop and one on Wednesday, January 27 on backcountry run "Sound of Music." Beginning late Friday, January 29 and into Saturday, January 30, the Park City Ridgeline received 14" of storm snow containing 1.1" of water, overloading the buried layer of faceted snow that formed in November and December.

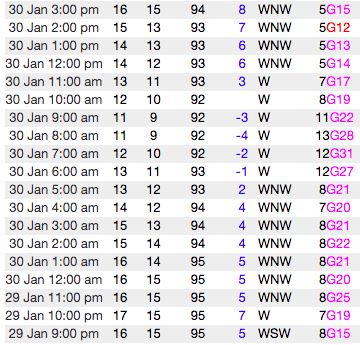

The table below shows the weather conditions at the PCMR weather station 9990, approximately 1/3 mile south of Square Top, for the 18 hours before the accident:

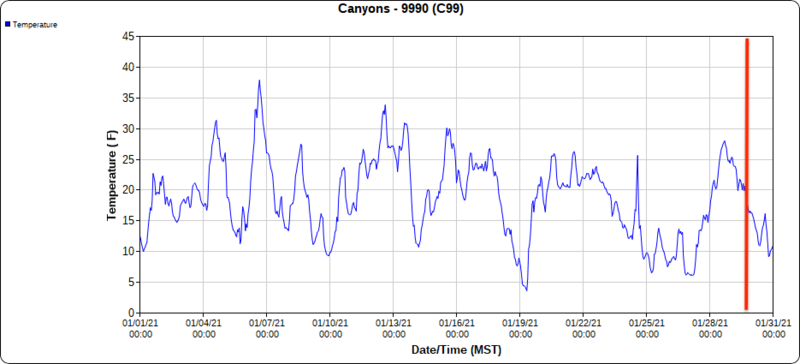

The first two graphs below show the temperature and wind profiles for the month of January from the 9990 weather station (el. 9990 feet), approximately 0.7 miles to the south. The red line is the approximate time of the avalanche.

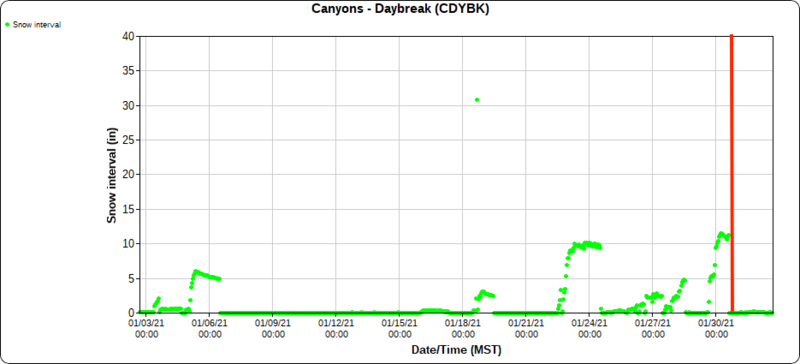

The graph below shows the snow interval (amount of snow with each storm) for the month of January from the Daybreak weather station (el. 9250 feet), approximately 2 miles to the southeast. The red line is the approximate time of the avalanche.

Snow Profile Comments

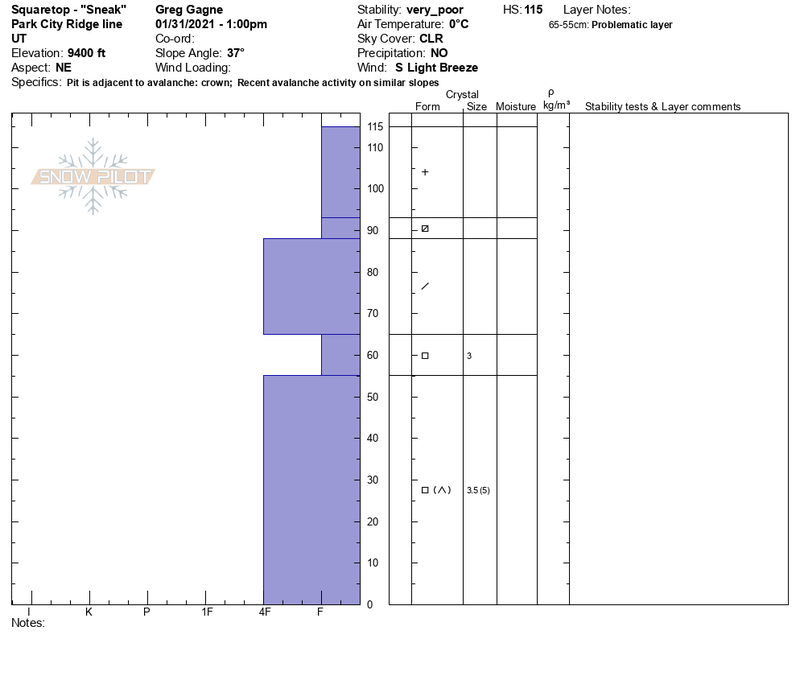

This snow profile was taken on the crown adjacent to where the victim had entered the slope. The slope steepness was 37°, and the depth of the crown was 2'. The weak layer the avalanche failed on was a layer of faceted snow at 60 cms.

Comments

We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims. All of us at the Utah Avalanche Center has had our own close calls and know how easy it is to make mistakes. No one is immune to this. We asked Kurt's partner what he wanted to share, and these paraphrased bullet points are what he said:

- When any group member feels uncomfortable about riding a slope, that unease should be enough for the rest of the group not to ski it as well. He regrets not being more forceful in his desire to stay off the slope that avalanched. It is common for people in a group to have different opinions on what they think they should ski or ride, and it is important to communicate and understand the reason for those differences.

- We often practice avalanche rescue as if we start at the bottom or the top. Consider practicing how you would perform a search starting at the side of the avalanche. The partner said it was difficult to know if the victim was uphill or downhill from where he started his search.

- He was extremely grateful for everyone who helped with the rescue.

- They knew they were entering the backcountry when they exited the gate at the resort and were aware that if an avalanche happened it was their responsibility to conduct their own rescue.

*Final note from Kurt's partner - "I want to share my belief that COVID had an impact on this accident. I realize now that I am exhausted from the 10+ months of near-constant stress COVID brings with worrying about my family, my friends, my work, etc. Plus financial stress, school closures, no physical contact with family members/friends, and so forth. As a result, my typical training, motivation, and mental reflection has been much less than a normal fall/winter. "

Information in this report was collected from Park City Mountain Resort Ski Patrol and Summit County Sheriff's Office. Additionally, Trent Meisenheimer, Greg Gagne, and Chad Brackelsberg visited the site the day after the accident during the recovery. Additional details about the sequence of events were provided by the victim's partner, who performed a heroic rescue by himself. Unfortunately, this avalanche was fatal, but the partner gave the victim the best chance of living that few people could have matched.

The staff of the Utah Avalanche Center sends its condolences to the family and friends of the victim.

Video

Coordinates