Observer Name

UAC Staff

Observation Date

Monday, October 28, 2024

Avalanche Date

Saturday, February 19, 2005

Region

Provo » Mt Nebo

Location Name or Route

Mt Nebo

Elevation

10,600'

Aspect

North

Slope Angle

40°

Trigger

Snowshoer

Trigger: additional info

Unintentionally Triggered

Avalanche Problem

Cornice

Depth

4.5'

Vertical

1,000'

Caught

1

Carried

1

Injured

1

Comments

Media report of a hiker that "rode 1000 feet in an avalanche feet first" bruised back and frostbit feet. Snowshoer triggered avalanche from the ridge when the cornice broke and he fell down on the slope.

Comments

Great Write up from Summit Post. Accessed October 28, 2024

Friday, February 18th Joe and I pulled to a stop at the mouth of Willow Creek Canyon shortly after 6:45 pm. We had just reached the unmarked trailhead for that weekend’s outing: a winter ascent of Mt Nebo via Cedar Ridge. Storms and high winds were moving in that weekend, with 1.5’ of snow forecasted for the mountains that night, but we had decided to go ahead with the trip anyway. Nebo’s Cedar Ridge was heavily forested until the last 1,500 ft before the summit, and the route would be on a ridgeline the entire way, rarely reaching a steepness that would have one concerned about avalanches. Because of the relative ease and safety of the route, we figured that it would be a safe route to do under the conditions, as long as we stayed on the route and avoided any questionable slopes.

As Joe and I got our gear ready, Casey hopped out of his car to greet us. Casey was a climber on Summitpost whom we had agreed to have along on the trip – he was heading up to the Wasatch to do some skiing and climbing and had expressed interest on an online thread about climbing Nebo via Cedar Ridge. After hearing about what sort of trips he had been on and reading about him in Scott Patterson’s latest trip report on their climb up CO’s Mt Massive, Joe and I welcomed the extra company.

We went over the route on the topographic map together and then headed up the steep slopes of Mt Nebo. We weren’t sure how far we were going to go up the mountain that night, but we had talked about camping either at 7,724’ or 9,000’. Casey had seen the mountain in the daylight before Joe and I had arrived and had noticed that there were a lot of cliffs barring access to the main ridge spur, so we headed up a side spur in hopes of regaining the ridge higher up.

The detour turned out to be a mistake – the clear terrain became brushy as we headed higher. Since Scott had reported on Summitpost that he never encountered much bushwhacking we suspected that we were off route, but continued on in hopes of regaining Cedar Ridge higher up. Joe began to express concerns about getting cliffed out as he reached a narrow point in the ridge. I looked down to the left and saw a large snowy clearing below that led to a long silvery tongue of snow that seemed to stretch from the valley all the way up to the camps we were hoping to reach. There was too much of a drop below to make descending to the flats safe, so I continued along the ridge to see if there was a better way to descend. Just as I reached a large cliff I saw that I could get down to the snow slopes below by down climbing some snow free rock just a short ways back from the cliff. The landing looked good, sloping away from the cliff, so in case I fell or needed to jump I was safe from falling off.

The scrambling was more difficult than expected – the rock was very steep and sharp. It was also a little slick lower down since there was a little snow on it. I grabbed a large flake and lie-backed as I moved down. Once I reached the end of the flake I found some knobby rock to grip on the underside, but beyond that there were no more handholds. I gripped the rock, lowered myself as far as I could, and failing to find any secure footholds, dropped the last 2 feet onto the snow slope. I called for the others to follow me down and then continued to break trail down the slope to a saddle joining Cedar Ridge to the spur that we were on.

“Oh my god!” Casey exclaimed once he reached the saddle. I had directed his attention back to where we had down climbed – he hadn’t seen the cliff earlier. The highpoint of the ridge and the cliff on the back side was large enough that I was able to identify it on the topo map. Our route had taken us to the brink of a sheer drop off. After a brief water break we headed toward the snow tongue only to find that the tongue was an old avalanche debris field – the snow was hard-packed and packed full of stones and snapped pine trees. The debris was very old and the current unstable slopes were on the north and east aspects at the time, rather than the south facing slope we were ascending, so I decided that a night-time ascent of the sliver was safe.

The snow provided a fast easy way up the slope, since the rest of the hillside was covered with thick scrub oak. Casey hadn’t expected such tough terrain on the first 3,000 feet of the route and had chosen to wear his lighter shoes at the time, and this made the going tough for him. Since he knew that we were close to a camping place by then, he chose to take off through the scrub oak toward a hopefully clear ridge rather than changing into his stiffer boots. Joe and I headed higher, taking occasional GPS readings as we ascended to keep track of our progress. Casey was tired from his long drive up from New Mexico and wanted to camp at the lowest camp, so we were going to have to leave the snowfield at some point to traverse over to the ridge.

I was a little overzealous in making progress up the hill, and suddenly we were at 8,100 ft. OOPS! Casey was too far away to hear us through the winds, so we bashed our way through the brush over to the ridge to explain the situation. Joe and I regretfully informed him that we had passed the first camp, but then I tried to talk him into climbing higher. I really didn’t want to lose and regain 400 ft, and by heading up to the next camp we would have that much less distance to cover tomorrow. Casey agreed to give it a try, with the understanding that we would head back down if the going got too tough. Luckily the ridge was clear and we made fast progress up the ridge.

At 8,400’ Joe and Casey found a nice campsite sheltered by some trees and the slope, so we dug our platforms for the tents and settled down for the night sometime around 11pm. Joe and I stayed up to have dinner and melt water, and by the time we went to sleep it was 2am.

Saturday, February 19th 6:00 am The howling winds had kept us awake last night, and occasionally a spindrift blew into the tent and onto my face. Still, we were well-rested enough to make a good summit attempt that day. As luck would have it the 1.5 ft of snow never appeared, so all that we had to look forward to was snow that was for the most part hard-packed. The wind scouring from the night before would make things even easier – our chances at making the summit looked good.

By about 8:00 am we had camp broken down and cached on the platforms to protect it from the wind. After marking a GPS coordinate to locate the cache upon our return, we headed up the ridge. We could see Mona far below, but soon we climbed above the cloud deck and were in a completely different world. The wind blew constantly at round 15mph with gusts up to 30mph, sometimes flinging stinging graupel into our faces. As the temperature dropped ice began to form on my eyelashes. The going was tough, but it was also exciting!

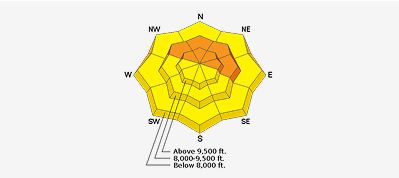

At 10,400’ we stopped for a brief snack. Tree line was finally making itself apparent and the more rugged parts of the ridge were beginning to appear. There were some small cornices overhanging about a foot and we took notice of these. Although visibility had deteriorated to a milky white after about 100 ft, we could still see some of the ridgeline ahead. By looking ahead we could see if there were cornices on the stretch ahead and how far back to stay. None of the cornices were very large.

Although we kept on eye on what we could see, we mostly trudged along mindlessly in the tracks of whoever was breaking trail at the moment. The air was thin, dry and cold, the graupel stung our eyes, and we were very tired. Since Joe and I weren’t as concerned about this route as we had been on others we had climbed earlier in the winter, we fell into a false sense of complacency.

11:00 am The ridgeline had become more open as the trees disappeared, but the slope was still very gradual, so everyone was still hiking with trekking poles – there was no need for ice axes. As the slope began veering further to the right we could no longer see the left side of the ridge ahead. This was the side that the cornices were forming on.

As I plodded up the slope I casually lifted my head up to take in what view I could when I noticed that we were walking parallel to the ridge, about 5 feet back from the edge. I also saw that the edge ended sharply – it was likely corniced. I began to worry since I had no idea how big the cornice was likely to be and was about to shout out to Casey that we should be staying farther away from the edge when suddenly it was already too late.

Avalanche Description

There was no sound from the cracking, and if I hadn’t been getting ready to move I surely would have been taken more by surprise. I saw a huge maw open up beside my right foot, and about all I had time to do was lunge over the gap. It felt as if I was being sucked downward, and my chest landed hard on the ridge. My arms were outstretched but there was nothing to grab on to – I slipped back and suddenly I was airborne. The slope below was so steep that I don’t recall feeling any impact. One moment I was falling and the next I was sliding, standing vertically on my toes as I tried to dig them into the slope. My snowshoes prevented me from getting much penetration in the snow, so I tried digging the handles of my poles into the slope, but by then I was rocketing down so fast that my efforts were futile. As I accelerated I could do nothing but kick and claw harder at the slope.

Everything happened so fast that I barely had any thoughts or feelings as I fell apart from “I must stop myself before I reach a cliff or tree” and “I’m going to die”. I fought as hard as I could but nothing seemed to work. Everything was white around me and all I could here was a low rumbling sound of my body whipping down the slope. There was a brief moment that I was airborne again – I was going off a cliff! Then I was sliding again, and then I was airborne again. I didn’t fall far but the brief loss of contact with the slope started to pitch me back and to my left. I spread my arms and legs out further and strained with my legs and back to fight the overturning forces pushing me down the hill. By some miracle I was able to keep myself upright and facing into the slope.

Finally I was beginning to slow down. I was now sliding through a cushion of snow that was getting thicker and harder, but it seemed to be slowing me down! I was still frantic at the thought that I might accelerate again off of a cliff or down another steeper pitch in the slope, so I made the best of this deceleration and tried to swim up and out of the snow as I kicked my feet into the slope.

Suddenly it was all over. I was no longer sliding. I brushed off a few inches of snow that was still covered me and stood up to take account of the situation. I was alive! Miraculously my only injuries seemed to be a slightly sore left quad, side and Latissimus Dorsi which were probably strained as I tried to keep myself upright and close to the hill as I fell. Then the severity of the accident hit me – I was in the middle of a gigantic avalanche debris field. Chunks of snow stretched away from me as far as I could see. I looked at my topo map to get my bearings – I had fallen around 1,000 vertical feet! Through the ghostly clouds and wind I faintly heard some shouting from above. Joe and Casey were all right! I couldn’t make out what they were saying and I was still out of breath, so all I could manage was a single loud yelp – “YEAH!”

I thought about where I was and realized that I was still NOT in a safe place to be. Rather than being on the safe wind-scoured southern slopes of Cedar Ridge, I was now at the bottom of a large, open snow bowl. Based on the aspect of the slopes above me, I knew that the side of the bowl closest to me was north-facing, corniced, and had had heavy wind-loading from the past 24 hours. Other avalanches could easy be washing down into the bowl!

The safest option I could think of at the time was to climb back up the way I had slid down. That slope had already avalanched, so it should be relatively safe compared to the rest of the slopes. Besides, I was still a little delusional in thinking that I could just climb back out. Sure it was about 1,000’, but I had all day, and maybe the upper slopes weren’t as steep as they looked on the topo!

I climbed up the ridge, but I was so pumped full of adrenaline and fear of further avalanching that I couldn’t keep a sustained pace. I kept getting exhausted and would stop every couple of minutes to rest. During these stops I tried to make contact with Joe and Casey. I was still rattled enough that I forgot about the emergency whistle in my pack, so I wasted breath shouting as loudly as I could. Because of the winds I didn’t know if Joe and Casey had heard my earlier response – I was worried that they thought I was dead! Throughout my time climbing back up the chute I never got a response.

My shouting echoed strangely, and as I ascended I saw why. Alongside the slope I slid down was a HUGE cliff! I let out a slew of exasperated cursing and kept climbing up the hill. The debris field seemed like it would never end. Finally I reached the scoured bed surface and encountered another surprise – a large gash in the slope, perhaps 15 feet wide and about 2 feet deep. Whatever had avalanched had ripped out this gouge clear down to the underlying talus! This was probably one of the parts of the slope that sent me airborne. For some reason I got out my camera to photograph it – perhaps it was an over learned reaction. About 50 feet higher I saw another gouge. Then I reached a continuous crown that was a few inches thick. The chute had a slight convexity in the center, so the crown had extended to the convexity, and shot straight up the slope for quite some ways before finishing its release to the other side. Just in case anything else came down the chute I stayed on this convexity in hopes than any further slides would wash to the sides.

The slope steepened and the bed surface became harder as I passed two more crowns. The slope seemed to be around 40 degrees now and I could barely kick steps, so I switched from my snowshoes to my crampons and got out my ice axe. As I front-pointed up the slope the ground got steeper and I became more concerned – if the snow was really getting as hard and steep as it seemed, then I probably couldn’t climb out!

Suddenly I saw a dark line in the clouds – was this a rockband? As I got closer I could see the wall with greater clarity. It too was a crown, but this one was almost as deep as I was tall!! I guessed that it was around 4.5 ft deep since it was about as high as my shoulders. It was monstrous, snaking like some evil serpent as it wound its way up the convexity like the earlier crowns, disappearing into the clouds above me. To the side of me I saw a foot-thick slab within the crown that had slid partway out beneath the snowpack, but friction had held it suspended. HANGFIRE! Now I was really nervous. I climbed a little higher and saw that the thick crown at fractured into some thinner crowns on the other side of the convexity, allowing me to wind my way between the slabs. At this point I lost my nerve to climb out this way. I had been climbing up the chute for an hour, but by now I didn’t care about making that wasted time.

I carefully but quickly backed down the slope and within about 20 minutes of continuous movement I reached the end of the cliffs beside the chute. I pulled out my topo map to look at my next course of action.

1:00pm Looking at the topo I saw that I might be able to walk down the canyon. It looked like there was a possibility of it cliffing out, and I would end up a long ways north of Willow Creek. I doubted that I would be out before nightfall if I went that way. Also, I was worried that Joe and Casey were heading out, and I was anguished at the thought of the news of my likely death reaching my family – I HAD to get out and get in touch with them before something like that happened!

Finally I spotted a route that seemed safe and possible. About half a mile down the canyon the slopes were heavily forested and they also looked less steep than the slopes surrounding the bowl that I was in. There was a slight ridge on that slope and it met up with Cedar Ridge at about 10,400 ft. I remembered that point on the ridge! The terrain on that part of the ridge looked thickly forested and didn’t appear too steep. I traversed down the canyon, praying all the while that I didn’t set off any slides above me. I stayed a little high near the base of the cliffs but on a low angled slope. Every now and then I had to cross a break in the cliffs, and I did so quickly.

As I hiked down through the swirling white, graupel began to rain down. As it fell, the graupel didn’t stick to the slopes like snowflakes would. Instead, the balls of snow just rolled down the slopes, piling up in depressions and on flatter inclines. So much graupel was rolling down from above that the air was alive with a hissing sound. Every now and then I ran into a thick patch of graupel, and although I was now hiking in my snowshoes, I sank in up to my waist in these little ball bearings. It was like wading through an exploded beanbag.

Finally trees emerged from the clouds and my hopes began to rise. The forest became thicker, but the snow became softer. I had to face into the hill on some traverses to keep from sliding down through the deep powder, but at least I was safer! As I looked up the slope I could make out rocky ribs rising above the treetops – definitely not the place to head back up. I could tell that it would be difficult to tell when I should start climbing back up.

Eventually I reached deep and narrow chute cutting down the slopes. I couldn’t get into the chute because it was lined with cliffs, making the last 10-20 feet or so quite impassable. On the other side was a heavily forested ridge that rose as high as I could see. This might be the way out! I followed the cliffs down a ways until I could find a drop that looked safe enough to descend. The snow was too steep to get purchase, so I stepped onto small pines lining the chute. I would hang onto the tree as I lowered/slid down to the next small pine, and repeated the process until I could slide the last few feet into the bottom of the chute. Then I ran across and tried to climb out the other side. Once again the snow kept sluffing off, so I had to pull myself up the slope by grabbing some of the small pines sticking out of the snow. Finally I was out of the chute and on the ridge!

The ridge was very steep and the snow was very loose. I tried to snowshoe up, but as I pulled snow down I soon ended up chest deep in the stuff without having made any upward progress – I was only digging myself deeper into the hill. Through a combination of jumping and swimming with my forearms and poles, I was able to get through the easier parts. In the more difficult snow I had to pack down as much snow as I could, kick a step as deep as I could and as high as I could, plunge both poles into the snow above as deep as the handles. Then, as I pulled and then pushed down on the poles, I slowly raised myself on one leg, careful not to collapse the step. Once my leg was extended I replaced my poles higher, one at a time, and began working on placing the next foot.

Progress was agonizingly slow, and sometimes it took several minutes to cover a few feet. The snow was so unstable that any rushing caused footholds to collapse, and it was a total body workout to make any progress up the hill. Finally I got a rhythm down, and occasionally I reached short patches of snow stable enough to just walk on. My heart had been beating furiously since I had fallen and I never seemed to be able to catch my breath - I always felt like I was about to be exhausted, but after a short break I always seemed to find the strength to move on. Picking resting points at landmarks every 20 feet or so seemed to help make the climb more psychologically manageable.

Finally the sky above the trees turned lighter and I caught a glimpse of the ridge above. I was going to get out! I pushed extra hard during the last bit and soon I was back at our tracks on Cedar Ridge ridge.

4:40pm I reached the ridge at 4:40. By then I had remembered my whistle, so I blew on it in hopes that Joe and Casey were somewhere on the ridge where they could hear it. I hadn’t drunk any water since the fall, so I forced myself to drink some before racing down to camp. Once I got there I saw that everything had been cleared out – they guys were on their way down. From my vantage point I could see our cars 3,000 ft below. There were a lot of other vehicles there too. Since we hadn’t parked at a real trailhead I doubted that these vehicles were those of other hikers – it was SAR (Search and Rescue)!

Finally I had cell reception back, so I called my father. I got the voicemail, so I said something to the tune of “Hi Dad. It’s about 5:00 and I’m calling to let you know that we’ve been delayed a little bit on getting down the mountain, so we won’t be getting home by late afternoon like I said we would. We’ll probably be home sometime late evening. I love you, bye!” I admit that was a vague message, but at the time I didn’t want to scare him since I was fine, and I figured that if he then heard about the accident he would know that I was all right since I gave the late time that I had called.

I knew that Joe didn’t have his cell phone on him, and I didn’t have Casey’s number, so next I called Shelley, Joe’s wife.

“Hey Shelley, have you spoken to Joe lately?” She was well aware of the situation and was thrilled to hear my voice. I told her that I was all right and to tell everyone to call off the search. Then I raced down the ridge.

A few minutes later Casey called me on my cell phone. I answered as I hiked down the mountain. He was relieved as I told him that I was racing down the mountain, nearing the 7,724’ flats and to call off the search. Luckily the rescue helicopters were still en route and were turned back. I told Casey that I should be down within an hour.

6:15pm I was practically running down the hill as I got closer to the bottom. My boots were loose and my toes were ramming into the toe-boxes, but I didn’t care. I slipped and fell a few times on some slush that was still melting on the talus. A little embarrassed, I hoped that I was high enough that the rescuers in the parking lot didn’t see me tripping over myself.

I was heading down a wash about a quarter-mile from the trailhead when I saw searchers heading up through the brush. I hopped onto a rock and waved my poles in the air to get their attention. I hurried down to them and was immediately inundated with questions.

“Do you have any aches or pains?”

“Just a little soreness in my back and right side.”

“We saw you falling down a few times up higher, are you all right?”

“Umm, yeah.”

“Did you have any loss of consciousness?”

“No. But I’m very dehydrated. Can we get some water out of my pack?”

Everyone rushed around me and they were almost overbearing in their care as they ‘assisted’ me in sitting down and taking off my wet outer layers of clothing. I was getting hot on the way down and had opened them to ventilate, so I was a little irritated when they replaced my hot clothes with a warm jacket, but at least it was dry. The mood was quite light as we strolled down to the car. The rescuers talked about some nice hunts they had had in the Willow Creek area as we walked down the hill. I didn’t have time to be reunited with Joe and Casey as I was herded right into the back of the ambulance.

Ultimately the paramedics found nothing seriously wrong with me. My heart rate was very high and I had a lot of adrenaline in my system, as was expected. My left foot turned grey and went numb as the adrenaline subsided. My feet were re-heated but because my big toenail was black and took longer to recover, there was a concern of frostbite, so I was taken to a hospital in Nephi for a follow up examination before being released.

The news media had caught wind of the rescue and were on the scene at the trailhead. Channel 4 followed me to the hospital and tried to pressure me into an interview as I hurried to the getaway car that Joe was driving, but I managed to escape. Apparently even though I refused to talk to reporters and hadn’t given consent to report on me in any way, all of the stations were running reports on the incident. None of them had all of the information correct, but all of them were using my full name. As I drove home with Joe I thought that everything was over and I could put it behind me, but I couldn’t get any relief. The Today Show and ABC’s Good Morning America wanted to interview me, and one of the New York offices had called my mom in Texas to get her comment about the accident, even though I hadn’t yet told her about it.

Ultimately I decided to appease the media by doing an interview with Good Morning America since I was rather ambivalent about the situation apart from worrying family and friends, but by then everyone was already well aware of the accident. After checking with Joe and Casey on how much anonymity they wanted, I went ahead and sat for an interview with ABC. Apparently even though they advertised the interview on the evening news broadcast, the interview was never broadcasted on Good Morning America. Somewhere between mudslides in CA and UT, a girl recovering from rabies, the world’s tallest twins, and a sexual harassment lawsuit involving Coco, the Gorilla, I lost out. Frankly, I’m just glad its all over – I’ve really just wanted peace and quiet since the accident, and I’m eager to have the media hoopla forget about me as quickly as possible so I can get on with my life.

Self Analysis of Accident

After the accident Joe and I talked about what had happened, and looking back on the incident we can see what we should have done differently to have been better prepared for the accident, and to have avoided it all together.

Communication: I had a cell phone to call for help if needed, but I was the only one with a cell phone on the mountain, so when I fell, Casey and Joe couldn’t call out for help until they got down to the cars. They also couldn’t try to reach me on my phone to determine my condition. I had brought 2 Motorola T5950 radios on the trip, but the intent was to practice with them for better communication on climbs where we would be traveling further apart. I had left them in the tent. In the future ideally everyone should have a radio and a cell phone if at all possible (in this instance we all could have brought a cell phone and a radio). For a more lightweight and reliable means of emergency communication, we all should have had emergency whistles and a predetermined set of codes by which to communicate with them (e.g. 2 blows for I’m OK, frantic blowing for HELP ME!!). I had a whistle, but that only limited me to blowing like a madman with no ability to communicate any better with others.

Complacency: Ultimately, what caused the accident was that Joe and I were too complacent on the route. Our largest concern on winter outings had been avalanches, and since the route was safe from such a danger (or we could recognize a danger if one did exist based on obvious terrain criteria) we let our guard down in just following the tracks of whoever was leading. On trips where we have been more nervous we’ve always looked around for ourselves, rather than just following the leader. In this instance that would have prevented us all from getting on the cornice as Joe and I would have made our observations of the danger BEFORE we were within 5 feet of the edge. In the future we’ll have to remember that when traveling in the winter back country, always travel like you’re leading.

Coordinates